Thanks for upgrading to a paid subscription. Writing is my job. Your support of that means everything to me.

I’ve come across two pieces this morning that deal with the question of grounds on which we might be optimistic about the lay of the land. One addresses the cultural level, and the other focuses on the public policy level. (The second one includes a respectful mention of me and a link to my recent piece “It’s Way Too Late For Keeping a Balls-and-Strikes Ledger.”

Ted Gioia’s Substack, The Honest Broker, is a frequent read of mine. We have done some of the same thinks occupationally (teaching and writing about jazz history, playing jazz) and he’s deeply concerned about a number of cultural trends, as am I, as you may have noticed.

So my curiosity was piqued by the sunny title of his latest post: “Indie Culture Is Great—But What's Coming Next is Better.”

He frames - properly so, on the level of addressing what had happened to big music corporations - the advent of the indie movement as an invitation to throw the doors of possibility wide open.

But - and I find this an interesting difference in our perspectives, since he’s only a couple of years younger than me - he sees what happened when the indie movement got underway as an exciting development. He sees the inflection point as being more recent, when human expression became “content” created for the purpose of having it go viral. I don’t disagree, but, crotchety Boomer that I am, I see the big problem with music as having gotten underway some time before.

Let’s let him frame it:

When I first heard the term indie music, I had no idea what it meant. At first glance, it seemed to involve tattoos, piercings, and hair colors not derived from any human DNA strands.

But I was wrong.

The word indie served as short hand for independence. And like those rebels who made a declaration under that rubric back in 1776, these uprising indie artists were rejecting all shackles and limitations.

It wasn’t just hair color. In the indie world, everything was now up for grabs.

Sometimes they called it alternative music—or just alt music. But the idea was the same. Conformity is over. Freedom is our future.

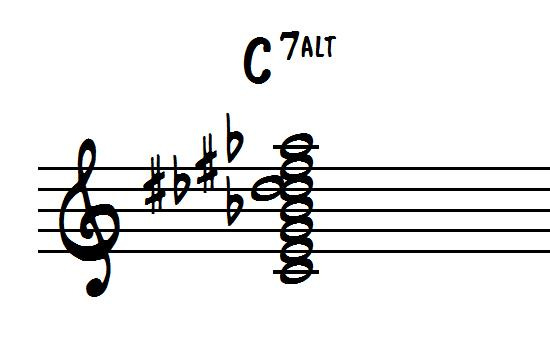

That’s a lovely vibe. But I still had no idea what an indie or alt song sounded like. The only alts I know about in music are alt chords—and the major labels outlawed those years ago.

So this alt music must be something different. But I could never quite define it.

Maybe that was the idea. When you declare independence from the plastic peoplerunning the show, you no longer need to follow any formula.

That lack of definition didn’t hurt indie artists and indie labels. For a few years, they were the hottest things in music.

And then it all stopped.

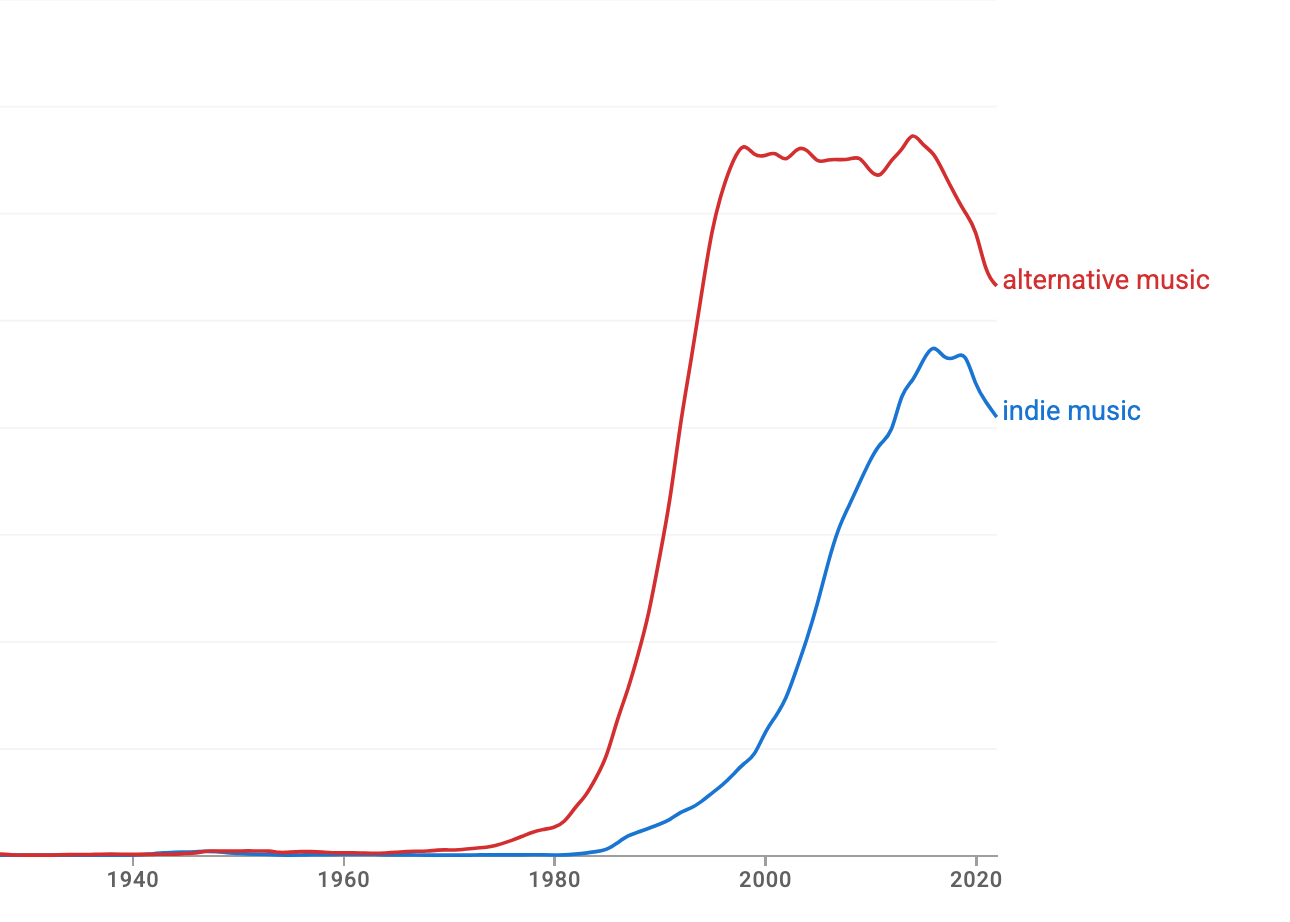

Judging by this chart of word usage, indie and alt music took off in the 1980s, and started declining sharply around 2013. By pure coincidence—or maybe not—that was the same year Spotify expanded into 55 countries.

But it wasn’t just music that lost its independence. The same thing happened in movies, media, and every other sphere of creative expression.

“We need something stronger than indie. And it’s starting to come to life.”

Huge digital platforms and devices promoted a culture of conformity. That was intentional. You can’t build a scalable global quasi-monopoly unless you get all the people on the same app—following the same rules and getting managed by the same algorithms.

The goal after 2015 wasn’t going indie. It was going viral. And by definition, virality is only achieved when everybody consumes the same memes and culture products.

Here’s the word usage chart on going viral:

I note that a pesky virus might have contributed to this. So let’s look at other markers of culture conformity—namely influencing and memes.

These charts capture a world of pain in just a few images. They show a shift from declaring independence to following the crowd.

Even worse, the dominance of the meme platforms has destroyed most of the creative ecosystem. Everything feels tired and exhausted in this new culture of regurgitation.

That’s not just my opinion. It’s a reality—measured out in the collapsing stock prices of companies that once set the tone for our leisure time. Disney stock is down 40%. Nike stock is down 60%. Warner Bros Discovery has collapsed more than 80%.

Even companies that once championed indie values have lost their mojo. Do you remember when Apple told everybody to Think Different? It’s hard to believe, but that once seemed like a plausible motto for Silicon Valley.

Not anymore.

Nowadays Apple is using the catchphrase “Built for Apple Intelligence.”

Now, for my own experience with the indie phase.

In my small Midwestern city in the mid-1990s, there was a woman who owned a recording studio where a blues band I was in cut a demo. I got to know her a bit, and she invited me to a dinner in nearby Bloomington, Indiana with some other arts writers and invited us to join her launch of a website called Indie-music.com.

Indie-music.com fairly quickly became a powerhouse. It included worldwide databases of venue owners and their contact information. Ditto management agencies and record labels. Much of the site was devoted to album reviews. It became a matter of prestige for indie artists to have a favorable review there. I know because the acts would lavishly thank me when I had a favorable assessment of their work.

What we were doing on our end was as seat-of-the-pants as the way the musical acts were making their records. Once a month, Suzanne’s mom would drop off a grocery sack full of CDs on my porch. Suzanne told me to just look through them and, on the basis of whether the covers promised anything appealing, review as many as I had time for.

I should note that the gig paid pretty nicely, in the overall scheme of my freelance writing work. Suzanne’s boyfriend Paul did some admirable work lining up advertising.

But back to the music I had to listen to. Over 50 percent of it was abysmal. The singer-songwriters were overly gooey, the post-punks laid on the nihilism impossibly thick, the experimental types seemed to be plying their craft for their own amusement.

(In fairness, I ought to state that there is one album, from 2012, and one song off that album, that continues to stand out as an unmitigatedly great piece of work. Listen here to “Marlee” by The Local Tourists and see what you think.)

But I contend that the problem of popular music’s purpose being distorted goes back a lot further. See my post titled “The Laurel Canyon Scene Was a Cesspool of hedonism, Self-absorption and Nihilism,” in which I take a square look at what a bunch of feral animals the oh-so-sensitive singer-songwriters of the 1970s were.

And how about The Beatles? Much discussion of their albums that has occurred in the last several decades focuses on their last three: the white album, Let It Be, and Abbey Road, and how they’re stunning masterpieces. Sorry to throw a curmudgeonly wet blanket on that take, but, as someone who began devouring their work in February 1964, I see those last three records as making it plain that the four members were tired of being The Beatles. Their manager, Brian Epstein, had died in June 1967, and, in lieu of his guiding hand, they hooked up with show-business accountant Allen Klein. John Lennon left his first wife, and his second one got him addicted to heroin. The four of them went to the Himalayas to immerse themselves in Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Mediation, only to find themselves disillusioned pretty much immediately afterward. John Lennon had seen the Maharishi make a pass at Mia Farrow’s sister, and, on the plane ride back to Britain, drank heavily and became obnoxious. Ringo Starr walked out on the white album sessions at one point, as did George Harrison during the Let It Be sessions.

No, The Beatles’ best recorded work is from 1962 to 1967, when the songs adhered to the 32-bar AABA form that had been the standard for popular music going back to Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.” There was a constant freshness to it. You could tell it was the work of four twenty-somethings who were experiencing something unprecedented, and found it thrilling.

But along about the turn of the decade, listeners and artists alike came to insist on a kind of “authenticity” that upended aesthetic standards. If an artist was tired of his or her career, we wanted to hear about it in song. We wanted them to air the dirty linen of their relationships. You found it in rock, pop, country and even to a certain extent in jazz.

So I cannot quite concur with Gioia that the popular-cultural atmosphere was fine at a certain point after that. And I wonder if he’s taking into sufficient account the atomization of post-American society. I doubt there can ever again be an overarching notion of what great popular music is. Earbuds and Spotify have truly buried Larry Lujack and Murray the K, not to mention Ed Sullivan, Arthur Godfrey and Arturo Toscanini.

Now, on to the second piece.

At Carrying The Fire, John Grady Atreides has a reflection on how to view the deteriorated state of post-America’s two viable political parties titled “On Calling Balls and Strikes.” He sees that as the only fair and realistic way to assess the current situation:

I fundamentally believe it is the writer's duty to be honest, and that means calling balls and strikes. When Democrats do something praiseworthy, I will praise them. When Republicans do something praiseworthy, I will praise them. My punditry is often negative, and since so much of oxygen is taken up by the current administration and the extra-large figure of President Trump, I spend a lot of time criticizing Trump.

I have to wholeheartedly agree with something he says shortly after that:

To be honest, I don't see much to like in either side. There aren't very many figures in American politics whom I trust to do what is right and to carry on the work necessary to restore the health of our constitutional system. That said, I also have more faith in our constitutional system than many doomsayers on right and left, and historical perspective compels me to point out that we have been in far graver danger before than we are today. The system we inherited from Madison and Hamilton is designed not to achieve perfection, but to let us survive more or less as a free nation. We have done that so far, and continue to do that. I’m neither optimistic, nor pessimistic about the future (I’m largely agnostic about what will happen), and so I will continue to call balls and strikes as I see them, rather than pretend I can predict what path we will take based on current trajectories (often a fallacy).

But, per his qualification of that, he has more faith in our constitutional system than I do.

He then makes the reference to me:

Some in my camp are growing nervous about the state of American society (including my fellow traveler, Barney Quick), and there is much to cause this nervousness. But temperamentally, I’m with Calvin Coolidge (who, as Rob from Robert Newton Peck’s Soup and Me pointed out, was the greatest president because he was from Vermont): “If you see 10 troubles coming down the road, you can be sure 9 will go in the ditch and you have only one to battle with.”

If I have any significance degree of faith in our constitutional system, it’s because the judicial branch of the federal government seems to be holding pretty well. Judges from across the political spectrum, appointees of Reagan, Bushes I and II, Clinton, Obama, Biden, and even Trump himself, have been forthright in calling the Very Stable Genius’s executive overreach what it is: egregious, lawless, and brazen.

Trump’s tariffs, being imposed on such friendly trading partners as Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, the EU and Mexico, are not only economically harmful. They isolate the US on the world stage. Leaders of those nations are coming to the conclusion that they are on their own and will have to form alliances without the United States.

They see that the US under Trump is completely unreliable in a situation like Russia’s ongoing rape of Ukraine. Yes, the Very Stable Genius “thinks [he’ll] have a major announcement” on the subject tomorrow, but none of us can forget the shameful spectacle of him telling President Zelensky, in the Oval Office, that Zelensky didn’t “have any cards,” and then sending him out a side door of the White House.

Trump is known for kidding on the square. Often, you’re not sure whether, or how much, to take any pronouncement of his seriously. The latest example is his social media post musing that he might revoke Rosie O’Donnell’s citizenship. Ha ha. Everybody knows he can’t do that. Okay. But his drool-besotted base has some new raw meat to get fired up about, and the bar for how US presidents discuss public figures that bother them has been lowered yet a bit more.

Consider the law firms that have caved to the VSG. Consider the rush Shari Redstone was in to unload Paramount (CBS News) before she had to get entangled in a lawsuit.

I realize that nothing is static in this universe. But I also know that influential figures and movements can set the tone for long-lasting periods of history. And precedents have been set in a number of ways on a number of levels that have done great harm to our ability to recognize virtues such as dignity, nobility, humility and the joy of our common humanity. Once a US president has publicly said that he hates members and politicians of the opposing political party, it’s hard to envision an upward climb in our discourse.

Maybe I am just a crotchety Boomer overlooking something major that ought to bolster my ability to see the glass as half-full.

If so, I’m happy to have it pointed out to me.

But sitting here in the comfort of my florid back courtyard on a Sunday morning, sipping my coffee and listening to a variety of summer sounds, I have a feeling that it’s happening on borrowed time.

Thanks for the response! I agree with much of what you say, especially regarding the judiciary and tariffs and Ukraine. Also, Beatles albums! I grow tired of the white album and Let It Be and find myself returning to the fun early stuff - Hard Day’s Night and great singles like “I Wanna Hold Your Hand.”