Thanks for upgrading to a paid subscription. Writing is my job. Your support of that means everything to me.

This one is going to require a great deal of care. Maybe the way to proceed is to state clearly at the outset that I am a Christian and it’s for that reason that I care a great deal about this subject. This won’t be the nitpicking of some cocky cynic. I understand what the Great Commission commands me to do.

But I’m keenly interested in obeying that command effectively.

And anyone with such an interest needs to grasp what a daunting task we have set before us.

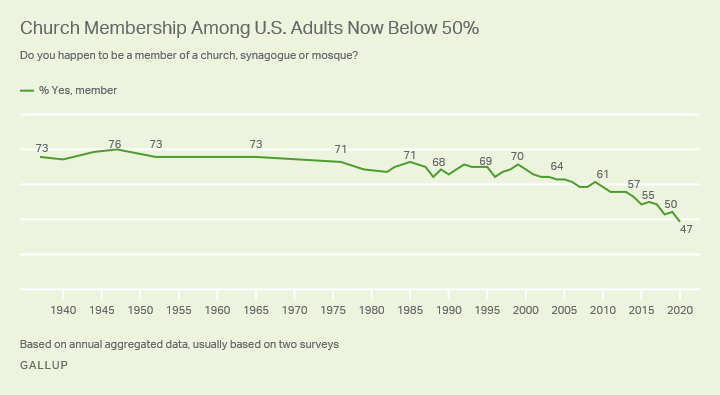

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Americans' membership in houses of worship continued to decline last year, dropping below 50% for the first time in Gallup's eight-decade trend. In 2020, 47% of Americans said they belonged to a church, synagogue or mosque, down from 50% in 2018 and 70% in 1999.

The excerpted article goes on to demonstrate it’s true for all living generations of US citizens - Greatest Generation folks, Boomers, Xers and millennials.

Well, it’s a 2021 article, so they didn’t include Gen Z, but you can be assured that the same phenomenon is true for that emerging bunch.

Longtime Precipice readers know that the inspirational fuel for writing posts is often a string of things I’ve come across in my first - sometimes second or third - daily perusal of the interwebs. A few items stick out as having a common thematic thread.

Such is the case with this one.

The first was a very recent (as in two days ago) confirmation of the statistical trend discussed above:

In the late 1940s, nearly 80% of Americans said they belonged to a church, synagogue, mosque or temple, according to Gallup. Today, just 45% say the same, the analytics company noted, and only 32% say that they worship God in a house of prayer once a week.

At The Times of Israel this morning, there’s an interesting piece examining two well-known figures who were raised in observant Jewish homes and as adults gravitated toward Christianity. They are New York Times columnist David Brooks and rock titan Bob Dylan.

Brooks has flat-out declared he’s a convert to the Christian faith. Dylan? He went through a “Christian” period forty-ish years ago, the apex of which was the powerful song “Gotta Serve Somebody,” which, in that razor-sharp incisive way Dylan has sometimes written - as opposed to the freewheeling imagery of, say, “Mr. Tamborine Man” - makes plain what he’s talking about. But in following decades, his work indicates a personal spiritual journey of a less defined nature.

The point of the Times of Israel essay is that both men, knowing what doctrinal Judaism teaches on the matter of a Messiah, have positioned themselves in sort of a mushy, unresolved no-man’s land.

The discussion brought to mind the conversation that arose out of Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s conversion to Christianity. The trajectory of her life story is notable. Raised Muslim in Somalia, she had a grandmother who made her undergo genital mutilation as a child. But her father was an intellectual and scholar who moved his family out of Marxist Somalia to various less hostile locales in Africa. As an adult, she settled in the Netherlands, became a Dutch citizen and served in the Dutch parliament. That’s when she really ran into trouble. She was outspoken about what Muslim immigration to the Netherlands was doing to the country’s sociocultural fabric. She moved to the US and became a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. She also decided she was an atheist.

And then she became a Christian. But she was taken to task for the Unherd piece in which she explained why.

The pretty-nearly-always-spot-on Carl Trueman of the Ethics and Public Policy Center gave her the benefit of the doubt which, since the essay in which he did so is pretty short, I will provide here in its entirety:

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a former Muslim and now a former atheist, recently declared that she has converted to Christianity. This is a cause for great rejoicing.

It is also a fascinating sign of the times. Her published account of why she is a Christian is somewhat odd, given that it mentions Jesus only once. It is, however, unreasonable to expect a new convert to offer an elaborate account of the hypostatic union in the first days of faith. This is why churches catechize disciples: Conversion does not involve an infusion of comprehensive doctrinal knowledge. And whatever the lacunae in her statement, the genuineness of her profession is a matter for the pastor of whatever congregation of Christ’s church to which she attaches herself.

Here is what makes her public testimony a sign of the times: She states that she converted in part because she realized that a truly humanistic culture—and by that I mean a culture that treats human beings as persons, not as things—must rest upon some conception of the sacred order as set forth in Christianity, with its claim that all are made in the image of God. “Western civilization is under threat from three different but related forces,” she writes. These are resurgent authoritarianism in China and Russia, global Islamism, and “the viral spread of woke ideology.” She declares that she became a Christian in part because she recognized that “we can’t fight off these formidable forces” with modern secular tools; rather, we can only defeat these foes if we are united by a “desire to uphold the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition,” with its “ideas and institutions designed to safeguard human life, freedom and dignity.”

The last few years have seen a number of unexpected voices strike hard against the mores of our time, particularly in the realm of sexual ethics and its close relative, the ethics of embodiment. Mary Harrington has written against the dehumanizing tendencies that lurk just below the surface of a society that sees transgenderism and transhumanism as legitimate. Louise Perry has pointed out that, despite its own propaganda about itself, the sexual revolution is very bad news for women and for children. Conservative Christians have, of course, been saying such things for years. But because Harrington and Perry are feminists and do not wear any obvious religious commitment on their sleeves, their voices have sounded louder and been more culturally shocking. As far as society is concerned, they should know better than the benighted simpletons of the religious world.

And now we have Ayaan Hirsi Ali. She too is concerned with how the West is dismantling its traditional cultural norms and with what it intends to replace them. Others have said similar things before. Philip Rieff and Sir Roger Scruton are two that come to mind. But the impression both of them leave is that, yes, they think God is a very good idea for grounding a civilized culture, but they are not entirely sure that he exists. What Ali has done is taken the obvious—and indeed necessary—next step: She sees the necessity of a sacred order and is not afraid to say so. It will be interesting to see if those others who have so astutely analyzed the sicknesses unto death that grip the West at the moment will follow her lead.

Yet there is a challenge here for Christianity: the perennial problem of the connection between the transcendent and the immanent, too often resolved in church history by instrumentalizing the gospel in the service of social activism. This has always been the vulnerability of liberal Protestantism, with its traditional support of the dominant moral consensus. Whether beating the drum for anti-communism in the 1950s or flying the rainbow flag from the church steeple in the 2020s, liberal Protestants do not so much offer prophetic criticism of secular power as provide a religiously informed idiom for its expression. The current progressivism, committed to the disruption of all stable categories, is a far more complicated creature to express through a Christian idiom—which means that much more of the traditional language needs to be jettisoned. Man and woman. God as Father. Jesus as male. All of these tenets offered little or no threat to anti-communism, but they cut into modern identity politics. And all speak to the lack of any sense of the transcendent, indeed any sense of the sacred, in liberal forms of Christianity.

Liberal Protestantism is dying, however, with mainline denominations fracturing and disintegrating at a striking rate. And today, we must also be careful that the truth of the gospel is not instrumentalized in the service of a different cultural campaign—even, for instance, a cause as worthy as that of opposing the leftist culture warriors who seek to overturn everything from parenthood to women’s rights. The most striking omission in Ali’s testimony is the one thing necessary to prevent such: a sense of the transcendent. God does not exist because he is useful for combatting wokeness or any other threat to Western civilization. He is useful because he exists, in holiness and transcendence.

This is not meant to cast doubt on Ali’s testimony at all. Indeed, her words are a cause for rejoicing, not cynical carping. Hopefully they are also a courageous example that others who see the problems of Western culture as clearly as she does might follow. I write this merely to echo the emphases of the Apostle Paul, whose understanding of this world was rooted in his understanding of, and preoccupation with, the glories of the next. Even the collapse of Western civilization would be a light, momentary affliction in light of the weight of eternal glory that is to come.

When the latest chapter in Hirsi’s odyssey occurred last year, it spurred some soul-searching in me. Precipice readers know that the premise from which I start is that set forth by the folks Trueman mentions: Hirsi, Roger Scruton, and Philip Rieff. Western culture - indeed, its basic common assumptions - are rotting at the foundation. But being concerned about that is not the same as saying yes to Jesus, is it?

And that is, of course, the essence of what He commanded us to persuade others to do just before he ascended into Heaven.

Which leads me to another item I ran across this morning that posits that Evangelicalism is a new thing in Christianity, distinct from Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Protestantism.

Wait, you might say, hasn’t evangelicalism been around for a while?

In a sense, but here’s what that author means (and, once again, I reprint an entire piece; it’s necessary for where I want to go next):

A few days ago, I came across an intriguing framework for understanding the development of Christendom from a Reformed Anglican or Presbyterian perspective. The author of this framework laid out what has long been recognized by serious students of church history: Christendom has historically encompassed three main branches:

Orthodoxy

Catholicism

Protestantism

The author suggested that a fourth branch, Evangelicalism, has now emerged, distinct in its characteristics and identity from the traditional three. Reflecting on my own 20 years as a Christian, 10 of which I’ve served as a pastor, this framework resonates deeply and, I believe, accurately captures the trends within modern Christianity. Here’s why.

While Evangelicalism emerged out of Protestantism, it has diverged significantly. It often bears more in common with the Anabaptist tradition, characterized by a radical individualism, than with the historical streams of Presbyterianism, Anglicanism, or even Lutheranism. This fourth branch has developed specific traits that distinguish it from the historical Protestant heritage.

Key Characteristics of Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism has emerged as a distinct movement, exhibiting twelve general characteristics:

Followers of Jesus – Rather than identify with historical Protestant labels or creeds, many within this movement prefer terms like “followers of Jesus,” shying away from traditional affiliations with either denominations or confessions.

Nondenominational Identity – Evangelical churches often choose to remain non-denominational or to minimize any denominational ties. Names like “Baptist” or “Church of God” are frequently removed to convey independence from historical church traditions.

Charismatic or Pentecostal Leanings – Charismatic and Pentecostal spirituality, including practices like speaking in tongues, prophesying, and faith healing has become common within Evangelicalism.

The Bible Only (Solo Scriptura) – Evangelicals tend to interpret Scripture apart from the interpretive lens of church history, operating on a “Solo Scriptura” basis rather than the Protestant doctrine of Sola Scriptura, which affirms the authority of Scripture while respecting the historical wisdom of the church.

Mere Christianity – This movement often advocates for a “mere Christianity” approach, emphasizing core doctrines like the Trinity, incarnation, and resurrection but avoiding stances on issues such as church polity, women’s ordination, or the role of sacraments, which are integral in the Protestant tradition.

Noncreedal – Most Evangelical churches avoid formal creeds, such as the Apostles’ or Nicene Creeds, and do not adhere to Reformed confessions like the Westminster Confession of Faith. Instead, they adopt basic statements of faith that lack the theological depth found in historic Protestantism.

Nonliturgical Worship – The Evangelical worship style is typically informal, devoid of structured liturgies or the sacramental focus characteristic of the Protestant tradition.

Contemporary Worship over Hymns – Rather than the rich hymnody or psalm-singing of historic Reformed worship, Evangelical services emphasize contemporary praise music, reflecting a shift from the doctrinal content of hymns to a more emotive worship experience.

Nonsacramental Theology – Evangelicalism often treats ordinances like the Lord’s Supper as symbolic memorials rather than as means of grace. Reformed churches affirm that in Communion, we experience Christ’s real presence, but Evangelicals generally approach it as a personal or communal statement of faith rather than an encounter with Christ’s grace.

Congregational Polity – Evangelical churches usually adopt an independent, congregational model, lacking the episcopal or presbyterian governance structures that provide accountability and connection to the broader church tradition.

Revivalism – Revival meetings, worship nights, and altar calls aimed at generating conversions and personal rededications are hallmarks of Evangelical practice, contrasting with the Reformed emphasis on covenantal worship and discipleship over emotional appeals.

Megachurch Phenomenon – Evangelicalism has seen the rise of megachurches led by prominent pastors who often become central figures in their congregations, contrasting with the Presbyterian focus on shared elder leadership and accountability.

Implications for Reformed and Anglican Churches

Understanding these characteristics sheds light on why there is often tension between Evangelicalism and the historic branches of Christendom. The nature of Evangelicalism’s independence and individualism has led it to evolve away from historical Protestant values, creating a unique branch that is largely unanchored to the traditional foundations of Protestantism.

For Reformed pastors, this framework offers clarity when members express a desire to integrate these Evangelical practices. There is a subtle pressure to adopt Evangelical methods—“Pastor, let’s host a revival to attract more people,” or “We could update our worship by doing away with the hymns and formalities.” These suggestions, while well-meaning, reflect an underlying departure from the Reformed ecclesial identity, which is rooted in Scripture, the sacraments, and confessional integrity.

The original author of this framework laid out these characteristics neutrally, but I find this description illuminating for why so many Reformed churches are struggling to retain their identity in the face of a culture steeped in Evangelical values. As pastors within the Reformed Protestant tradition, it’s vital to recognize this emerging Evangelical branch as distinct from our heritage. Knowing this, we are better equipped to reassert our historical and theological commitments, ensuring our congregations remain faithful to the doctrines and practices of Reformed Christianity in the midst of modern shifts.

Okay, here’s what I mean by needing to proceed with care. I want to refer you to point 8 above. Modern praise music indeed genuinely speaks to a great number of people whose faith is steadfast. But I am a musician. I consider the ability to make music one of the greatest gifts with which God imbued the species he fashioned in his image and likeness. Bach was a church organist, and it informed the elegant logic with which he crafted his melodies and harmonies. He lifted his compositions heavenward as a thank-you for what he had been given. I’ve written before about the ability of the great hymn writers - Isaac Watts, William Cowper, Charles Wesley, Fanny Crosby - to stir hearts and articulate God’s glory in timeless ways.

Here’s how I dealt with this in an August 2021 post here titled “I Never Feel Like Waving My Arms”:

There’s also contemporary praise music. About that: I can’t stand contemporary praise music. It goes hand-in-hand with the rhythmic arm-waving that has become a staple of so many worship services. Many start with it, and it tends to go on and on. And on. I have done the Emmaus Walk and participated in some jail ministry, both profound experiences that had lasting impact. I felt a sense of brotherhood with those I shared those weekends with in the core of my heart. It’s inextinguishable to this day. But, in each case, when the house praise band got onstage, my reaction was, sheesh, again?

And that has led to a question with which I’ve grappled for a few years now. Why aren’t I more demonstrative about my faith?

It’s not so much lingering doubt anymore. I’m done with cynical dismissals and gotcha questions. I have no patience with atheist snark. It reeks of a desire to assert superiority, which is hardly a mark of mature engagement with life’s most pressing questions.

No, I’m quite willing to concede that where I still encounter sticking points, the onus is on me to dig deeper. That’s principally because, for all the institutional rot in so many denominations and boneheaded means of evangelizing, the people I respect the most in this world and in history have been deadly serious about their faith.

But I find the most useful approach for so digging is apologetics. It hones my steadfastness to ponder ringing yet respectful defenses of the Christian truth against objections.

Paul set the pattern when he addressed a crowd in Athens:

22 So Paul, standing in the midst of the Areopagus, said: “Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. 23 For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. 24 The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man,[a] 25 nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything. 26 And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, 27 that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him. Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, 28 for

“‘In him we live and move and have our being’;[b]

as even some of your own poets have said,

“‘For we are indeed his offspring.’[c]

29 Being then God's offspring, we ought not to think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man. 30 The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent, 31 because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.”

He allowed that their search to date had been earnest and, indeed, had revealed to them some valuable insights. Only then does he say that the God they’ve been feeling their way toward (I love that phrase) can be truly known.

Origen’s Contra Celsum, written circa 248 A.D., provides us with a fine model for responding to not just objections but attacks on Christianity. Celsus, a secular philosopher who not only thought the faith was a lot of hooey but harmful to society, had written The True Word, a book-length explanation of his views. Origen took the time to address Celsus’s points one by one with rigor but also courtesy.

Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions is an account of how he came to see the folly of being driven by lust and an attempt to convince himself that his intellect was a sufficient guide. He contributed greatly to Christianity’s understanding that, while human beings are imbued with free will, there is a right use of free will to which they become compelled to turn once they heed God’s beckoning.

Pascal’s Wager takes an interesting approach, namely, asserting that the stakes are too high to not believe in God. Pascal was one of those guys who has to be heeded, given that he was no slouch in a number of fields besides theology, such as mathematics, physics and philosophy.

In more modern times, C.S. Lewis’s Meditation in a Toolshed is a classic in the field of apologetics. I return often to his notion of looking along the beam:

I was standing today in the dark toolshed. The sun was shining outside and through the crack at the top of the door there came a sunbeam. From where I stood that beam of light, with the specks of dust floating in it, was the most striking thing in the place. Everything else was almost pitch-black. I was seeing the beam, not seeing things by it.

Then I moved, so that the beam fell on my eyes. Instantly the whole previous picture vanished. I saw no toolshed, and (above all) no beam. Instead I saw, framed in the irregular cranny at the top of the door, green leaves moving on the branches of a tree outside and beyond that, 90 odd million miles away, the sun. Looking along the beam, and looking at the beam are very different experiences.

But this is only a very simple example of the difference between looking at and looking along. A young man meets a girl. The whole world looks different when he sees her. Her voice reminds him of something he has been trying to remember all his life, and ten minutes casual chat with her is more precious than all the favours that all other women in the world could grant. lie is, as they say, “in love”. Now comes a scientist and describes this young man's experience from the outside. For him it is all an affair of the young man's genes and a recognised biological stimulus. That is the dif- ference between looking along the sexual impulse and looking at it.

When you have got into the habit of making this distinction you will find examples of it all day long. The mathematician sits thinking, and to him it seems that he is contemplating timeless and spaceless truths about quantity. But the cerebral physiologist, if he could look inside the mathematician's head, would find nothing timeless and spaceless there - only tiny movements in the grey matter. The savage dances in ecstasy at midnight before Nyonga and feels with every muscle that his dance is helping to bring the new green crops and the spring rain and the babies. The anthropologist, observing that savage, records that he is performing a fertility ritual of the type so- and-so. The girl cries over her broken doll and feels that she has lost a real friend; the psychologist says that her nascent maternal instinct has been temporarily lavished on a bit of shaped and coloured wax.

As soon as you have grasped this simple distinction, it raises a question. You get one experience of a thing when you look along it and another when you look at it. Which is the “true” or “valid” experience? Which tells you most about the thing? And you can hardly ask that question without noticing that for the last fifty years or so everyone has been taking the answer for granted. It has been assumed without discussion that if you want the true account of religion you must go, not to religious people, but to anthropologists; that if you want the true account of sexual love you must go, not to lovers, but to psychologists; that if you want to understand some “ideology” (such as medieval chivalry or the nineteenth-century idea of a “gentleman”), you must listen not to those who lived inside it, but to sociologists.

The people who look at things have had it all their own way; the people who look along things have simply been brow-beaten. It has even come to be taken for granted that the external account of a thing somehow refutes or “debunks” the account given from inside. “All these moral ideals which look so transcendental and beautiful from inside”, says the wiseacre, “are really only a mass of biological instincts and inherited taboos.” And no one plays the game the other way round by replying, “If you will only step inside, the things that look to you like instincts and taboos will suddenly reveal their real and transcendental nature.”

That, in fact, is the whole basis of the specifically “modern” type of thought. And is it not, you will ask, a very sensible basis? For, after all, we are often deceived by things from the inside. For example, the girl who looks so wonderful while we're in love, may really be a very plain, stupid, and disagreeable person. The savage's dance to Nyonga does not really cause the crops to grow. Having been so often deceived by looking along, are we not well advised to trust only to looking at? in fact to discount all these inside experiences?

Well, no. There are two fatal objections to discounting them all. And the first is this. You discount them in order to think more accurately. But you can't think at all - and therefore, of course, can't think accurately - if you have nothing to think about. A physiologist, for example, can study pain and find out that it “is” (whatever is means) such and such neural events. But the word pain would have no meaning for him unless he had “been inside” by actually suffering. If he had never looked along pain he simply wouldn't know what he was looking at. The very subject for his inquiries from outside exists for him only because he has, at least once, been inside.

This case is not likely to occur, because every man has felt pain. But it is perfectly easy to go on all your life giving explanations of religion, love, morality, honour, and the like, without having been inside any of them. And if you do that, you are simply playing with counters. You go on explaining a thing without knowing what it is. That is why a great deal of contemporary thought is, strictly speaking, thought about nothing - all the apparatus of thought busily working in a vacuum.

The other objection is this: let us go back to the toolshed. I might have discounted what I saw when looking along the beam (i.e., the leaves moving and the sun) on the ground that it was “really only a strip of dusty light in a dark shed”. That is, I might have set up as “true” my “side vision” of the beam. But then that side vision is itself an instance of the activity we call seeing. And this new instance could also be looked at from outside. I could allow a scientist to tell me that what seemed to be a beam of light in a shed was “really only an agitation of my own optic nerves”. And that would be just as good (or as bad) a bit of debunking as the previous one. The picture of the beam in the toolshed would now have to be discounted just as the previous picture of the trees and the sun had been discounted. And then, where are you?

In other words, you can step outside one experience only by stepping inside another. Therefore, if all inside experiences are misleading, we are always misled. The cerebral physiologist may say, if he chooses, that the mathematician's thought is “only” tiny physical movements of the grey matter. But then what about the cerebral physiologist's own thought at that very moment? A second physiologist, looking at it, could pronounce it also to be only tiny physical movements in the first physiologist's skull. Where is the rot to end?

The answer is that we must never allow the rot to begin. We must, on pain of idiocy, deny from the very outset the idea that looking at is, by its own nature, intrinsically truer or better than looking along. One must look both along and at everything. In particular cases we shall find reason for regarding the one or the other vision as inferior. Thus the inside vision of rational thinking must be truer than the outside vision which sees only movements of the grey matter; for if the outside vision were the correct one all thought (including this thought itself) would be valueless, and this is self-contradictory. You cannot have a proof that no proofs matter. On the other hand, the inside vision of the savage's dance to Nyonga may be found deceptive because we find reason to believe that crops and babies are not really affected by it. In fact, we must take each case on its merits. But we must start with no prejudice for or against either kind of looking. We do not know in advance

whether the lover or the psychologist is giving the more correct account of love, or whether both accounts are equally correct in different ways, or whether both are equally wrong. We just have to find out. But the period of brow-beating has got to end.

Boston College philosophy professor Peter Kreeft’s approach really sticks to my ribs.

How’s this for a consideration to chew on?

Someone once said that if you sat a million monkeys at a million typewriters for a million years, one of them would eventually type out all of Hamlet by chance. But when we find the text of Hamlet, we don't wonder whether it came from chance and monkeys. Why then does the atheist use that incredibly improbable explanation for the universe? Clearly, because it is his only chance of remaining an atheist. At this point we need a psychological explanation of the atheist rather than a logical explanation of the universe.

I need this kind of bolstering when I fold my hands and drop to my knees, principally because I need my Christianity to have an aspect of being raw, of deadly seriousness.

I want my devotion to be built on that foundation of which Christ spoke in the parable of the house that could withstand hurricane-force winds.

I understand that a lot of those today with the most steadfast faith have come by it due to a personal-level life event: the depths of addiction, the death of a child, being on the receiving end of a horrific crime. That’s not how it happened for me. It’s true that I have recently come through a pretty nasty health downturn, but I still need to be reminded on the level of my restless, barely tamable mind that, no matter what possibilities I might entertain, there is no avoiding Him if I am to ever find peace.

So a major question before the believer in our time is, how does one share the Truth we know?

Some thoughts:

Read the person as accurately and thoroughly as possible. With most post-Americans, you’re probably going to need to take your time getting to any mention of Lord Jesus. Take a cue from the above-mentioned apologists. Start with letting the person you’re talking to articulate the basis of how he or she finds meaning in life. You likely only have one shot with a lot of people to whom you want to evangelize. Know what is going to turn them off and end the conversation. I speak from experience. For the decades during which I was an agnostic with a vaguely mystical inkling of what ultimate reality is all about, my reaction to being handed little pamphlets about “the good news” and how I don’t have to be destined for Hell was along the lines of “save that stuff for somebody else, pal; I’m not interested.” Start where the person you’re talking to is.

Don’t be a prude. Post-American society is an arena characterized by coarseness and a veneration of the bizarre. Don’t be afraid to hear and see a lot of behavior and appearance that we know clearly runs counter to the notion of basic human dignity. That’s where we are. Many great Christian authors’s works - I think here of examples such as Dostoevsky and Flannery O’Connor - are full of depictions of sin - lust, envy, petty divisiveness, murder. They show that real, unshakeable faith is hard-won. Iron sharpens iron.

On the other hand, stay away from emulation. A lot of folks who are former addicts and / or criminals like to wear their tattoos and piercings as evidence that they have come through the fire, as well as that the church door is open to all without judgement. Okay. As I say above, we must meet people where they are. But we must show those whose interest we have engaged that the journey moves beyond clinging to sobriety like a little piece of rock above the surface of a stormy sea. God wants us to grow in the use of our natural gifts, whether they be artistic or of a STEM-related nature, or dynamic forms of meeting human needs. He wants us to rekindle our intellectual curiosity. Regain and refine our sense of humor. God likes full human beings.

Make sure you know why you’re doing any worker-bee-type activity. And I say above, I’ve done some jail ministry. I’ve worked in a food pantry and delivered Christmas dinners to shut-ins. Packing boxes of food, setting up chairs in a meeting space, organizing vacation Bible school and such are, on one level, merely physical activities not unlike those with a secular purpose. Don’t let disagreements over how the chairs are arranged, or what the characters in a VBS skit are going to be called, get in the way of the premise. Community outreach is ministry. When you get involved in it, you are the hands and feet of the Lord. Serious stuff.

Don’t just sell your faith on the grounds that it will merely be comfort to the person you’re en gaged with. While you don’t want to go about it boneheadly, as in the handing-of-a-pamphlet example cited above, at some point, find a way to appropriately convey the point that this whole matter is as high-stakes as it gets. It may take a while. You may have to be very deft about getting to the matter of the person having a soul. But eventually that has to be part of the conversation.

I hope I’m not writing about this in a way that comes off like I see myself as a highly evolved big shot. Far from it. I’m working all this out for myself as well.

But the stakes are indeed high. For you and me and the unbeliever. And for the civilization we assume will keep us safe, comfortable and ever-advancing. That’s unlikely unless we get to work. And even then, remember that it’s not our permanent home.