Tuesday roundup

A taste of some important essays I've come across recently

Thanks for upgrading to a paid subscription. Writing is my job. Your support of that means everything to me.

Not sure what the weather’s doing where you are, but here, we’re having a glorious rain after a fine stretch of brilliant blue skies and even more brilliant fall colors.

Alas, the next phase of the season is upon us, and bare trees don’t look quite so stark in a fine autumn downpour.

And if you’re not confined to an artificially lit cubicle saddled with a lineup of teleconferences or reams of data to manipulate, consider spending the day with a nice cup of Earl Gray, a blanket, and some important reads curated by Precipice.

(Or, if you are in that cubicle, perhaps you can surreptitiously carve out sufficient downtime to peruse these recommendations.)

He begins with a dire assessment of the current lay of the land:

We are living through a civilizational inflection. The West is gravely ill. It is not yet time for hospice. Palliative care is required. Palliative medicine treats serious illness and multisystem failure; it manages pain when the cure is uncertain. That is our cultural condition—moral, institutional, political, economic, ecological, and spiritual systems all failing at once, without clarity on what to do next.

Our leaders prescribe optimism: innovate, pivot, build back better. They offer marketing slogans instead of addressing reality. But a culture cannot heal when it refuses to name its disease.

The late sociologist Philip Rieff called our moment a Third Culture—a social order that has severed its link to the sacred. First Cultures, in his analysis, lived within mythic transcendence; Second Cultures, such as Christendom, drew moral authority from revelation. The Third Culture rejects both. It affirms freedom without form, choice without covenant, progress without purpose, overwhelmed with information without the capacity to live within a meaningful, orienting story.

He notes four attributes of a culture, and analyzes what we have done to each:

Civilizations unravel along their deep structures—those unseen frameworks that make meaning possible.

First, culture is a reality of its own, not a sum of individual choices. Evangelicals often treat culture additively: change enough hearts, and society will follow. But culture multiplies; it interacts; it has emergent properties. James Davison Hunter, in To Change the World, warned that all theories of cultural change based on individual conversion will fail. Culture is a social fact, as French sociologist Émile Durkheim insisted a living organism that shapes us even as we inhabit it.

Second, culture is hierarchical. Religion is upstream from culture; culture is upstream from politics. Religion forms the moral order; culture expresses it; politics institutionalizes it. When the sacred collapses, every downstream institution wobbles. Rieff captured this simply: culture is the form of the sacred order.

Third, culture is coercive. It shapes conduct long before law demands it. Try publishing a defense of gender biological reality in The New York Times and you will learn how social taboos punish other views.

Finally, culture is invisible until it fails. We live in it as fish in water. When the sacred evaporates, the social atmosphere thins; meaning suffocates. Rieff warned that “the death of a culture begins when its normative institutions fail to communicate ideals of the sacred.” Ours have failed.

Modernity replaced being with having, mystery with mechanism. Reality became a do-it-yourself project; persons became data; communities became markets; nature became inventory, storytelling became story-selling. The sacred once ordered the social from above; now politics dictates culture, and culture manufactures its own religion. We have traded transcendence for technique, worship for branding, truth for polling. The soul has become colonized by algorithms.

The reversal is complete—and catastrophic. God created man in His image. Now man perceives he can create God in his image or replace God with AI surrogates.

Since you really ought to read the entire piece, I’ll leave you with some choice lines that will compel you to do so:

“AI is the left brain’s dream: tireless, precise, and soulless. It promises omniscience while eroding discernment, information without wisdom.”

“ . . . the more godlike our power, the more precarious our position.”

“Fashion Models and Sports Teams, metal to folk music, Hollywood films, and Silicon Valley apps preach a common creed: autonomy as salvation.”

“Earlier ages clashed over rival gods; we live or attempt to live with none.”

‘We begin by telling the truth: that our culture is ill; that its disease is spiritual; that its cure is repentance, not policy. We recover the humility to receive the world as a gift, the courage to resist its idols, to honor objective reality, and the imagination to rebuild on foundations of transcendence.”

At Front Porch Republic, Alisa Ruddell has us look at some sticky points regarding spontaneous abortion:

It was the fall of ‘99, and I was a freshman at a Christian liberal arts college overlooking the Hudson. The evangelical subculture I was steeped in was unquestioningly pro-life. One morning my favorite professor spoke to the entire student body in chapel, engaging us in a thought experiment.

Had we considered the implications of our belief that personhood begins at conception? he asked. Did we know how many embryos are miscarried every day, most unbeknownst to their mothers? And if these countless billions are innocent human souls made in God’s image, shouldn’t we expect they will be in heaven? And that means heaven is mostly populated by “people” who never lived beyond a few days or weeks in the womb? That embryo souls outnumber believing Christians by an astounding rate? That most of the redeemed never had a face, never had arms or legs, never had a brain, never took a breath, never read the Scriptures because they never had eyes, never heard of Jesus because they never had ears, and were never baptized because they never saw the light of day? What do we think of that kind of heaven? What kind of afterlife can you have if you slipped away from this life before anyone even knew you were here? How should we orient ourselves to the sheer magnitude of this continuous, invisible loss? What, precisely, is lost?

He didn’t say those exact words. I’m filling in the gaps in my memory with subsequent thoughts I’ve had along the lines he started. But his gist was a pin hovering uncomfortably close to my pro-life balloon. He wasn’t providing an answer: he was pointing out a theological problem. It wasn’t a question about heaven’s seating capacity but about what constitutes a “redeemable” person: how much of a “you” must you be to be part of the people of God?

At eighteen, my heart was a smooth, unbroken surface. The provocation my professor threw out couldn’t find purchase in a life like mine, without rough patches or cracks caused by suffering. His questions slid right off of me, and I promptly forgot about them. Within a decade, if I remembered that moment at all, it was with a wry shake of my head: There can’t be more embryo souls in heaven than conscious Christians with a testimony. And aren’t we all just magically thirtysomething in heaven anyway? Our bodies develop and change continuously in this life as we age—do our souls “age” along with us or are they static and complete from the get-go? My thoughts quickly spiraled off into speculation without moral stakes.

Alas, the passing of a few decades prepared her for a fresh look at the matter:

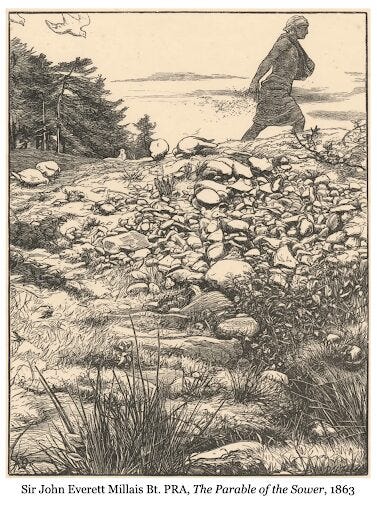

But the questions came back to me twenty-six years, two and a half decades of marriage, and four children later, on a day when my devotional reading of a parable coincided with tedious yard work that placed biological facts about seeds squarely in front of my face. I finally had ears to hear. My heart had been textured with painful experiences; I knew now how to sit with unanswered questions. The problem of the fragility, liminality, and sheer quantity of “wasted” embryonic human beginnings began to bother me. Instead of allowing myself to forget or to speculate, I dug in.

A bit later, she demonstrates that nature does not have a zero-waste policy where furtherance of species is concerned:

I read aloud Peter Wohlleben’s book The Hidden Life of Trees to my boys last year, and was stunned by what he calls “the tree lottery.” He doesn’t mention the rates for sweetgums, but a poplar (which produces over 54 million seeds in its lifetime) will end up producing only one descendent that reaches maturity. If you’re a plant seed, the odds are never in your favor. The overabundance of fertility—the exorbitant number of living lottery tickets—is the flip side of nature’s saturation with contingency, failure, and death. In a letter to J.D. Hooker, Charles Darwinmused, “What a book a devil’s chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering, low, and horribly cruel work of nature!” No kidding.

Trees are not the only organisms whose seeds and sprouts die for the sake of that rare lucky one which survives. Out of one thousand sea turtle hatchlings, one reaches adulthood. Common frogs have a 1-2% survival rate for their offspring. Baboons have early miscarriage rates of 60%. High rates of loss are not a glitch in the system, but a feature of how complex organisms reproduce. Such loss is baked into the process of bringing new life into the world.

Human propagation is not exempt from this:

Vast amounts of “seeds” are wasted in human procreation: roughly 733 billion sperm are spilled by the average married man over his lifetime (chatGPT did the math). As fetuses in their mothers’ wombs, females start with 6-7 million eggs: this drops to 1-2 million at birth, then 300,000 by puberty, and continues to decline over the reproductive years until there are fewer than 1,000 eggs remaining at the onset of menopause. This drastic culling of eggs for quality is called atresia. Gametes aren’t people, so this isn’t controversial to point out. But this should resituate us as part of nature’s lottery, since each individual is the combination of just one lucky sperm and one lucky egg meeting in just the right way at just the right time.

Wasted seeds don’t tend to bother us now, but many are troubled by the waste of fertilized “seedlings” (especially expectant parents and Christians). It turns out that natural early embryo loss—“spontaneous abortion” in medical terms—is just as likely an outcome as a live birth in humans. The odds of an embryo’s loss and a baby’s birth are roughly equal—a coin toss. Forty to sixty percent of human conceptions are naturally and spontaneously aborted by the woman’s own body, often before implantation, and sometimes occurring so early in the pregnancy that she never even knew she conceived. Perhaps her period is a few days late or just a bit heavier than usual. Perhaps she notices no difference at all.

As she zeroes in on her concluding point, she offers this nugget for our consideration:

Procreation and loss are inextricably intertwined in nature—and we are a part of nature. We can’t reasonably place spontaneous abortion into the bucket called the Fall. If we do, then all of human procreation goes in there too, because the success and the failure are a package deal. It’s impossible to be purely “pro-life” in the physical sense. You don’t have that kind of body. Even extreme admit-no-exceptions pro-lifers have choosy wombs. Anyone willing to welcome new life will get her hands “dirty” at those ineradicable checkpoints. There is a tragic hue to being human and to extending our family tree that neither scientific achievements nor religious idealism can expunge.

Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute asks the question that is often our preoccupation here at Precipice: “Can The American Right Find Its Way Back?”

Trump did display impressive and iconic leadership after he was shot last year. But that moment stands in stark contrast to the collapse of public dignity and the coarsening of political discourse that he has hastened. Just last month, the president of the United States posted an AI-generated video of a fighter jet dumping feces on Americans who oppose him. And again, where Trump leads, Republicans follow. Vice President JD Vance, for example, recently responded to a critic on X by calling him a “dipshit.”

Dignity, decorum, and seriousness matter in a democracy. Elected leaders who renounce them lose the confidence of those who are not already in their camp. It becomes more difficult for the country to come together to face adversity – be it a pandemic, a terrorist attack, an economic calamity, or a war – as leaders struggle to compromise to address policy challenges.

Under Trump’s watch, his MAGA (“Make America Great Again”) movement has served as a conduit for some of the ugliest forces in politics to make a run at the mainstream. Tucker Carlson’s recent interview of the Holocaust-denying, Hitler-admiring, white-nationalist, anti-liberal MAGA influencer Nick Fuentes was a case in point. Carlson has often used an aggressive interview style with opponents, but this time, he did not challenge his subject’s appalling and dangerous views. Nor was this the first time that Carlson had promoted anti-Semitism.

Mark Pulliam gives us a ringing expression of admiration for Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett at the Acton Institute’s Religion & Liberty webpage:

Many Americans wonder if any jurist on the U.S. Supreme Court will ever be able to fill the shoes of the late, great Justice Antonin Scalia, who passed in 2016. President Trump has—so far—appointed three avowedly originalist justices with the potential to do so. In her new book, Listening to the Law: Reflections on the Court and Constitution, Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett demonstrates that she has the intellect and judicial philosophy necessary to establish herself as a force on the Court in her own right.

Barrett’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Trump in 2020 was a dramatic moment, for several reasons. The vacancy she would be filling was created by the death of liberal icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg, affectionately nicknamed “The Notorious RBG.” Barrett’s nomination, on September 26, was only 38 days before the hotly contested 2020 presidential election. Democrats were still mad about Senate Republicans’ refusal in 2016 to schedule a confirmation hearing for Merrick Garland, President Obama’s stillborn nominee to replace Justice Scalia. (As President Biden’s uber-partisan attorney general, Garland proved the wisdom of Sen. Mitch McConnell’s resolve.)

The payback confirmation hearing for Brett Kavanaugh in 2018—nominated by President Trump to succeed the pivotal Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was retiring—was the nastiest in memory, combining the worst elements of the gauntlets unleashed on Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas. The nation was expecting comparable fireworks for the relatively unknown Barrett, a former Notre Dame law professor who had served for less than three years on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, with her chambers in South Bend, Indiana—not exactly in the national spotlight.

Yet the charming and unflappable Barrett dazzled the Senate Judiciary Committee—and the nation—with a masterful performance at her confirmation hearing, resulting in her being confirmed by a vote of 52 to 48 to become the only non–Ivy League law school graduate on the Court. She was smart, poised, and likable.

Barrett actually looked at a career path other than the one she pursued:

One theme of Listening to the Law is Barrett’s reverence for the written word. As a lifelong reader, in college she not surprisingly majored in English and considered pursuing a career as an English professor. “I didn’t grow up wanting to be a lawyer,” she admits. Before applying to graduate school, however, she had an epiphany. Law, like literature, relies on words but has real-world consequences: “Law governs the relationship of the government to its citizens and its citizens to one another.” Barrett chose law school instead and went on to be a star student, graduating first in her class.

Barrett’s reverence for the written word is reflected in the title of her book and her commitment to “textualism,” the interpretive methodology championed by her former boss, Justice Scalia, that gives primacy to the statutory text. (The constitutional counterpart to textualism is originalism.) In both cases, words matter.

A revealing insight into Barrett’s judicial philosophy comes early on when she relates an anecdote involving “a favorite aunt,” a political liberal who complained to Barrett that the Court’s opinions (including her own) were often driven by “legalities.” The aunt lamented: “Amy, I thought the Court was supposed to be about doing justice.” Many political liberals embrace such a view, which used to be known as advocating “the living Constitution.” Barrett’s anecdote provokes an extended reflection on the appropriate role of judges in a democratic republic.

Barrett explains that

we judges don’t dispense justice solely as we see it; instead, we’re constrained by law adopted through the democratic process. … It’s a unique role created and defined by the Constitution. … In our system, a judge must abide by the rules set by the American people, both in the Constitution and legislation. … Frankly, that takes self-discipline. … My office doesn’t entitle me to align the legal system with my moral or policy views. … If I decide a case based on my judgment about what the law should be, I’m cheating. … As Justice Scalia rightly observed, “The judge who always likes the results he reaches is a bad judge.” … Just as it’s a problem when a judge likes all the results she reaches, so too is it a problem if the judge wants others to like the results that she reaches.

Barrett provides a telling real-life example: Before she was a judge, writing as a Catholic legal scholar she expressed a moral objection to capital punishment; as a justice on the Court, however, she voted to uphold the death sentence imposed on Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the Boston Marathon bombers. As a judge, she followed the law, not her conscience, despite her moral reservations. And she expects other judges to do the same: “Whatever the source of the [judge’s moral] conviction, it cannot affect the outcome of the case.”

Hopefully, you have here a substantive way to pass this moist November day. Then again, you could distract yourself with “[f]ashion Models and Sports Teams, metal to folk music, Hollywood films, and Silicon Valley apps.” You were imbued with free will like me; I can’t make that choice for you.

I think there’s a logical fallacy in the article about abortion. It’s akin to arguing that because people die in accidents every day, it’s impossible for any culture to be pro-life. Death is a fact of life. Miscarriage is a fact of life. Neither of those facts implies that actively taking an innocent person’s life or actively choosing to abort a child is morally permissible. If I live in an apartment building where, unbeknownst to me, a man on my floor trips in the kitchen and hits his head on the edge of the counter and immediately dies, I have no moral culpability in his death. If I intentionally or unintentionally killed him, I would.